Eddie Htet Aung Lwyn: A Dose of Survivor’s Guilt, Recurrent Frustration, and Moments of Overcoming

Written by Kate Ngan Wa Ao

“Artistic Freedom for me is to create despite the government and the powers that be. It is honouring the purest part of a person who wants to create and speak truthfully to oneself. It has now become a privilege, even though it should not be. But it is a privilege I embrace with a dose of survivor’s guilt, recurrent frustration, and eventual brief overcoming of it.”

— Eddie Htet Aung Lwyn

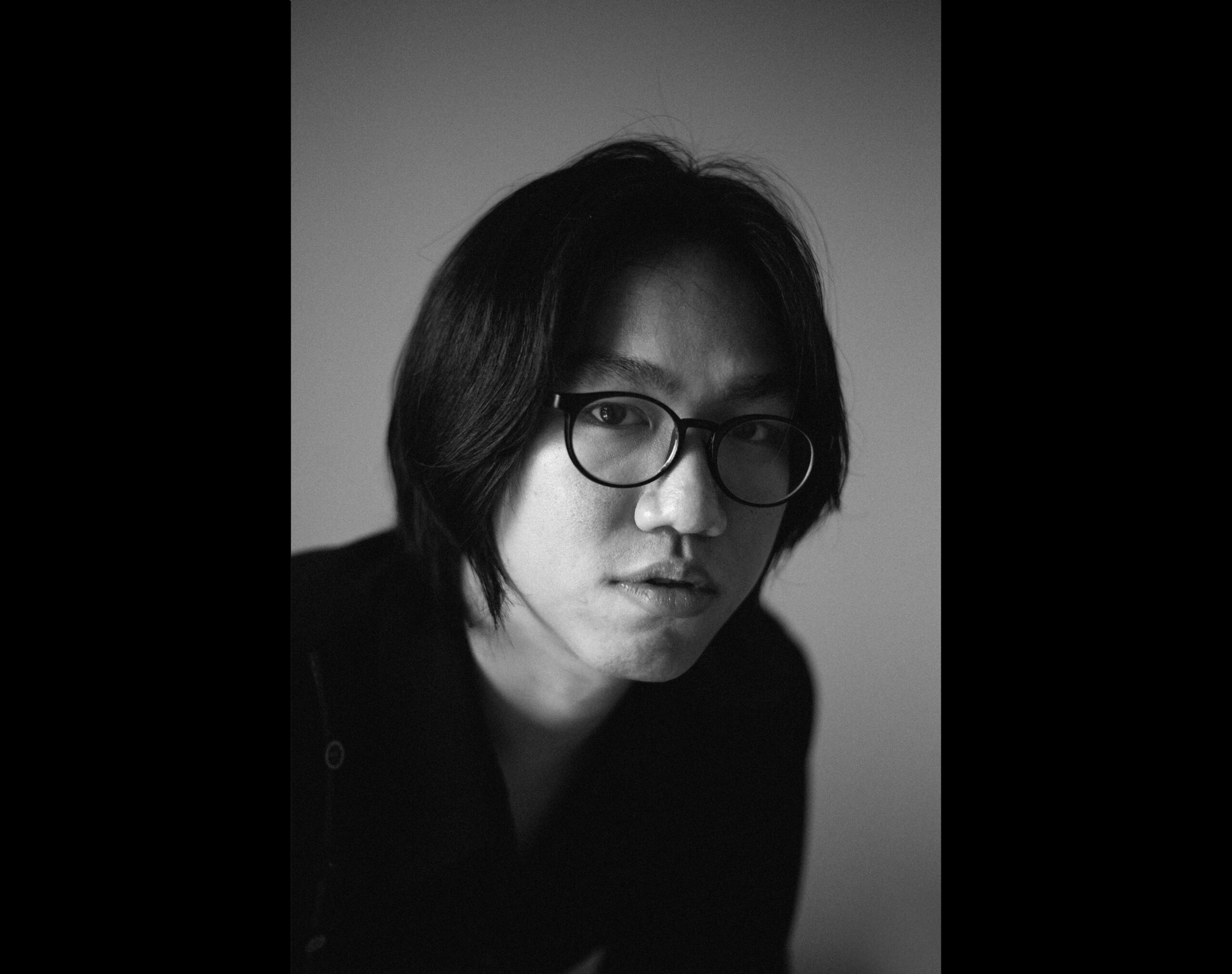

Eddie Htet Aung Lwyn (they/them), born in 1998 in Myanmar, have been in our residency programme Oslo Art Haven since June 2025. Eddie is a storyteller who works primarily with the languages of cinema and photography, though they identify first and foremost as a writer. Their work explores the complexities of gender and sexuality, as well as the transformation of identity through experimental storytelling.

Before 2021, Eddie gained experience working across various organizations and media platforms, including &Proud, a queer organization that celebrates LGBTQ+ lives and advocates for the decriminalization of homosexuality in Myanmar. In 2021, as the political situation in Myanmar deteriorated following the military coup, Eddie fled to Thailand with support from local organizations. They settled in Bangkok, where they began supporting newly arrived Burmese dissidents. They also worked as a researcher at Global Voices from the 2020 elections in Myanmar until 2023.

— I was doing all kinds of jobs in different organizations, researcher, translator, and more, because that was how I could justify leaving home while still feeling like I was contributing. I focused more on community work with other dissidents from Myanmar, as it felt more immediate and urgent. I put my creativity aside for as long as I could, until I no longer could. At the end of 2021, I quit most of my jobs to become a full-time artist, Eddie says.

In 2022, Eddie created a photography project titled Weight, which explored themes of displacement, survivor’s guilt, the burden of political unrest, and their own identity crisis at the time. The project was a success and has been exhibited globally.

They have since completed three short films: Return to Sender (2020), Where the River Ends (2023), and JuJu vs.The Possibilities of Life, Love, and Death? (2024). These films have been screened internationally at different film festivals

Telling Stories of Home From Afar

The stories in Eddie’s films are always set in Myanmar. However, since filming there is no longer possible, they are brought to life in Thailand. This raises a painful question: How does one create work about home while being forced to live away from it?

Eddie grew up in a community-oriented society, and being in a collective environment remains deeply important to them. Eddie would make a deliberate effort to involve Burmese people in their film crews, as many Burmese artists and filmmakers were also exiled to Thailand.

— When I am making a film, I am fully aware that it is not Myanmar, even though the story is set there. For example, in Where the River Ends, we filmed in a forest in Thailand. Because it was in a forest, it made us think: “This could be Myanmar, if we believed it.” That brought a sense of comfort. And that feeling only really came alive because we had Burmese people on the crew. I could hear the Burmese language around me all the time, and for a moment, it felt like home, Eddie recalls.

Leaving Home, Finding Self

In Myanmar, homosexuality and transgender remain criminalized under Section 377 of the Penal Code, a colonial-era law introduced by the British rule in the 19th century. Still in force today, it carries a punishment of up to 10 years in prison.

After leaving Myanmar, Eddie began to experience a sense of freedom from the country’s deeply homophobic policy and environment, but that freedom came at a cost, leaving behind the Burmese people, leaving home.

— It felt like two separate journeys happening simultaneously. Yes, I had to leave home; it was devastating, and living in exile carries a heavy burden of survivor’s guilt. But at the same time, I am finally able to dress how I want and be who I am as a queer person. Part of me feels liberated, safer, and freer. I am becoming a truer version of myself. And thankfully, along the way, I also found my community with other queer Burmese people in exile, Eddie says.

This dual experience of navigating identity, freedom, and belonging deeply informs Eddie’s work. For example In their film JuJu vs The Possibilities of Love, Life & Death? (2024). The story follows the protagonist JuJu, a Burmese trans femme working at an independent cinema in Bangkok. While there, she encounters another Burmese man, who may or may not have romantic feelings for her. What unfolds is a series of conversations and imagined scenarios in JuJu’s mind, exploring the power of queer representation in mainstream media, queer identity, stereotypes, and the search for love.

New Film Project – Explores Privilege

Eddie said the calm of Oslo is much needed after four years of chaos in Bangkok. They want to use this opportunity to focus on researching and developing the script for their first feature-length film, a thriller set in the 1940s during British colonial rule in Myanmar.

This project explores the complexity of colonization and its dichotomy: between the local who remains oppressed, and the fellow Burmese who returns from abroad, now seen as an outsider. Eddie explains:

— As one of the colonized, people are clearly oppressed, but within that, some start to see the colonizers as the model of ‘success.’ They start to learn their language, work with them, adopt their ways, and often get rewarded with privilege. In British-ruled Myanmar, many Burmese people worked alongside the British. They were given homes, education, and some were even sent abroad to study in England. My question is: does this make them less Burmese?

— While exploring this idea of privilege. I think about my own journey. My artistic career is, in part, ‘elevated’ because my people are being oppressed. If that weren’t the case, would anyone care what I have to say? Am I where I am because of my and my people’s trauma? I guess that is also one of the sources of my survivor’s guilt.

Freedom, Guilt, Heal

Feeling guilty is a complicated and often experienced emotion among exiled artists. Many carry a deep sense of guilt for being away from their homeland. For Eddie, this was no different. Does being an artist help ease survivor’s guilt, or does survivor’s guilt stem from being an exiled artist in the first place?

When Eddie first arrived in Thailand in 2021, survivor’s guilt became their main motivation for making art. It felt less like a choice and more like an urgent necessity. Eddie describes it as almost a physical response, like throwing up, an intense emotional release. They had no other choice but to make art to survive the heaviness they carried. That was when the photography project Weight was born.

— The survivor’s guilt is kind of the cause and the consequence. As an artist, I process my emotions through my art; that is how I cope with what is happening in the world. Guilt kind of pushed me forward. And frankly, in this industry, I would not be where I am without my guilt, because it was once my fuel to make work, Eddie reflects.

But now, Eddie seems to have found a new way to motivate their artistic practice, one rooted in acceptance and the celebration of community.

“Do I still feel survivor’s guilt? Yes, of course. But my motivation has shifted. Now, I want to create art as a celebration of being alive, of having survived, of being in community. I like to call it radical joy, because we all need it.“

— Eddie Htet Aung Lwyn

When asked how to find one’s way through freedom, guilt, and healing, Eddie believes there is no simple answer, as it is an extremely complicated matter, and everyone’s situation is different.

— I wish there were a formula for how to navigate the dilemma of freedom and survivor’s guilt. But there isn’t. Everyone navigates the world in their own way. Some focus on building a career or financial stability, and that is valid; others may feel a strong desire to return home and contribute there, and that is valid, too. Because every experience is valid… Eddie shares.

“Everyone navigates the world in their own unique way. We are all just doing the best we can with what we have.

We all heal in our own time.“

— Eddie Htet Aung Lwyn

Safemuse is looking forward to continuing our collaboration with Eddie and supporting their creative work during their residency with us.